The Last of the Kaiadilt: The Birth of a New Art

“My mother always sits and watches the sunset. I’m often busy, but she would tell me, ‘Go look at the sun, look at the sky, it’s so beautiful,’ and I go to watch her sunset. She stands there, as if memorizing every color—red and orange, her favorite colors. Then she says, ‘I’m going to paint this’.”

Berelina, daughter of Amy Gulatcha

Amy Loogatha (Amy Loogatha Rayarriwarrtharrbayingathi Mingungurra, or Amy Loogatha) was born in 1942 on Bentinck Island (Queensland, Australia). She is one of the few remaining members of the ancient Kaiadilt island people living in Australia today.

Now, at 82 years old, Amy Loogatha paints; her work is represented by several galleries in Australia. Amy Loogatha’s art is a burst of red and orange with touches of blue, white, and green.

Unlike many regions of Australia where Indigenous artists draw on long-standing iconographic traditions, such as rock art, bark painting, body painting, or sand drawing (as in Central Australia), the artists of Bentinck Island had no prior tradition of painting as such. The Kaiadilt women only began painting in 2005, but their art now holds a prominent place in contemporary Indigenous Australian art.

Late afternoon sun (c) Amy Loogatha. Courtesy of Mirndiyan Gununu Aboriginal Corporation, Mornington Island Art Centre.

The Island

Bentinck Island is 180 square kilometers of arid land and reefs in the Wellesley Islands archipelago, surrounded by the rich waters of the southern Gulf of Carpentaria, part of Queensland. The islands of the archipelago are low-lying, with beaches surrounded by mangroves, salt flats, and low shrubs. The life of the Kaiadilt clan (just over 100 people) has been simple for millennia, centered around the sea, the shore, and the sky. The sea is full of fish, dugongs, and turtles. The sky and shores are filled with birds of incredible colors. The Kaiadilt have been one of the most isolated tribal groups in Australia for thousands of years. They are the last coastal tribe in Australia to have sustained contact with Europeans, resisting the influence of colonial occupation until the very end.

The Mackenzie Massacre

Since European colonizers settled on the continent, Indigenous people have been consistently oppressed. Colonization led to a reduction in their numbers and the seizure of their lands. There is a list of killings committed by white settlers against Indigenous peoples, among which the Mackenzie Massacre on Bentinck Island in 1918 stands out. This crime is part of a series of mass killings that occurred after the formation of the Australian Federation in 1900. Prior to this incident, Sweers Island, located nearby, had been leased by the government to a man named Mackenzie, and part of Bentinck Island was also leased to him. After settling on the islands, he began shooting men and raping women.

In 1918, he gathered several other settlers from the mainland and organized a real hunt for the locals. They drove the Kaiadilt to the southern shore of the island; some fled into the ocean, while the rest were shot. This incident was not known to the public, and information about it only became widely known in the 1980s through the accounts of survivors. Mackenzie was never punished. One of the most valuable testimonies of these events is the book “The Mackenzie Massacre on Bentinck Island”, written by Kaiadilt representative Roma Kelly and anthropologist and linguist Nicholas Evans. The book details the incident based on the accounts of survivors.

Amy Loogatha, photo: Cooee Art Leven Gallery

The 1940s: New Upheavals

In the 1940s, the life of the Kaiadilt people changed forever when missionaries arrived on the island and began relocating the locals to nearby Mornington Island. A Presbyterian mission had been established there in 1914. After several attempts over the following decades to convince the Kaiadilt to leave their homeland, the missionaries succeeded in moving the last remaining families to Mornington in 1948. All forcibly relocated Kaiadilt were given shirts and trousers instead of their traditional garments and were assigned English names.

Artist Amy Loogatha was one of those children forcibly removed from the island. She was 7 years old when she was separated from her parents. In the new schools, they were told that they had been rescued after their native Bentinck Island was flooded by a tidal wave and that there had been no fresh water after years of drought. Surviving and grown-up Kaiadilt children later said in interviews that they believed this to be a lie. Many of the relocated children were very young, but many clearly remembered how the missionaries chained their tribesmen and forcibly loaded them onto boats. On Mornington Island, the children lived in dormitories for boys and girls, while their parents built humpies (huts) on the outskirts of the mission, gazing at their native Bentinck Island.

Mass Kidnapping or Evacuation?

Records of weather conditions in nearby areas show that the summer rains in 1946 and 1947 were within normal limits. However, a severe famine broke out on Bentinck Island. The year 1946 marked the culmination of several years of insufficient rainfall, leading to heightened tensions among the island’s inhabitants. Inter-clan conflicts resumed, and of the 96 people living on the island at the beginning of 1946, only 87 remained by the end of the year.

In late 1946 or early 1947, tragedy struck 14 of the 19 people, mostly from the second clan, when they set out on a raft to Allen Island and drowned. The survivors explained that they hoped to find better food there; at that time, water was not scarce. These five survivors were found by missionaries from Mornington, who were on Allen Island, and were transported to Mornington Island. When they were discovered, they were in critical condition due to lack of water and would likely have died if not rescued.

The last resident left Bentinck Island in October 1948. [ South Australian Museum; Public Library, Museum and Art Gallery of South Australia. Records of the South Australian Museum. Adelaide: Published under the authority of the board of governors and edited by the museum director, 1918. Vol. 14. [Electronic resource]. URL: <http://biodiversitylibrary.org/permissions> (accessed: 08.06.2024).]

Most deaths in the final year are attributed to the aftermath of a catastrophic event—an unprecedented tidal surge in February 1948. Coastal dunes were flooded, and sands were saturated with seawater, depriving the inhabitants of normal freshwater supplies. The last days of the remaining Kaiadilt on the island were marked by frantic searches for water frogs, which burrow into dried-up ponds during the dry season and emerge during the rainy season. Some of those rescued and relocated to Mornington died from the effects of their ordeal and stress.

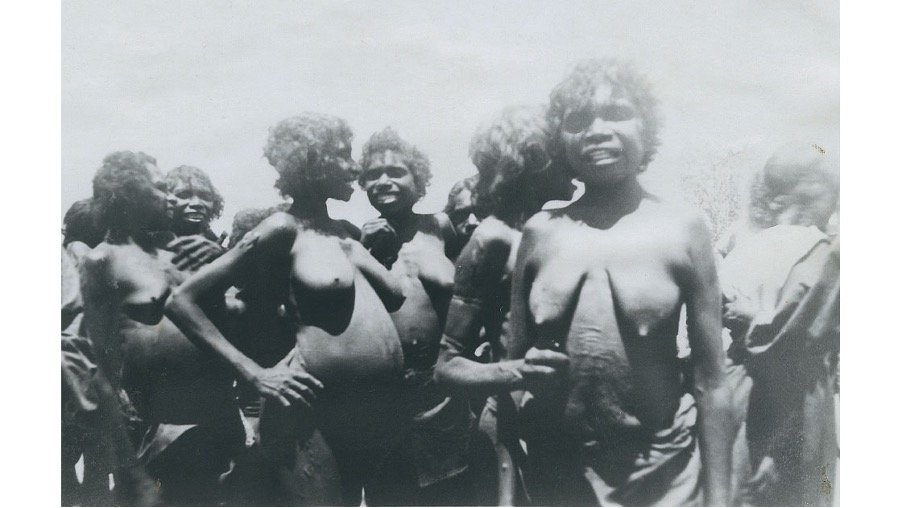

Arrival of a group of Kaiadilt women at the Mornington Mission, circa 1948, photograph by Mornington missionaries

Kaiadilt Culture and Art

The evacuation effectively marked the beginning of the destruction of both Kaiadilt culture and language. All children were confined to dormitories, living apart from their parents and relatives, and the transmission of language and knowledge was lost. On Mornington Island, they lived in a separate area, in beach huts facing their native island.

The Lardil people, the Indigenous inhabitants of Mornington, looked down on the Kaiadilt, oppressing them and denying them access to fishing grounds. Conditions were so harsh that for several years, children were either stillborn or died at their mothers’ breasts within minutes. The absence of children created a gap between generations. It would take at least ten years before a Kaiadilt child was born and survived. No one born after the relocation of the Kaiadilt mastered the language. For many Kaiadilt, it took nearly half a century before they could return to their ancestral lands, thanks to the gradual establishment of outstations (in Australian English—outstation, a part of a farm separated from the main farm), and most had to accept life in a demoralized ghetto on the outskirts of the Mornington Mission, where parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents suddenly lost the authority they had held as dulkuru dangkaa (a person who holds a place) on their own land within their tribe.

Unlike other Indigenous peoples, where art has played a significant role for millennia, the Kaiadilt never painted.

It all began in 2005 when the first Kaiadilt woman, Sally Gabori (1924-2015), picked up a brush for the first time at the age of 81. This happened because art center coordinator Brett Evans brought painting materials to the Mornington Island Art and Craft Centre. Her talent was quickly recognized. Today, Sally Gabori is recognized as the most successful Indigenous Australian artist. She represented Australia at the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013.

Other Kaiadilt women followed Sally, and soon the world began to speak of a distinct “school” and artistic style of the Kaiadilt. However, it is a mistake to speak of a formal school or direction of the Kaiadilt. Each artist’s style and choice of themes differ. If you ask the Kaiadilt to paint the same phenomenon or object, they will paint it in completely different iconographic manners.

Amy Loogatha is one of the recognized Kaiadilt artists and one of the few who have preserved the language. The sudden surge of creative energy came late in her life. Today (as of the writing of this article in 2024), she is 82 years old. She paints and is represented by several galleries in Australia. She is frail, living in a nursing home on Mornington Island, but she visits her native Bentinck Island as often as possible. During her lifetime, the greater part of the history of the colonization of her homeland has passed at an accelerated pace: from traditional life to contact with white people, from sudden and almost complete deprivation to her recent emergence in the outside world as a renowned artist.

What makes the Kaiadilt artists so important and special is that they represent such an individual and highly abstract development of a culture of vision, rather than a culture of painting. Each of them has invented her own, unique artistic language to show us how they see their world.

Place where two rivers meet (c) Amy Loogatha. Courtesy of Cooee Art Leven, NSW, Accompanied by a Certificate of Authenticity from Mirndiyan Gununa, Mornington Island Art

They use an extensive crossword of metonymic connections that may initially seem surprising to Europeans. Amy Loogatha’s painting Place Where Two Rivers Meet (Fig. 4) answers this question: where are the rivers? They are likely depicted through circles representing stone “walls”. Sometimes they are called “fish traps”, which trap fish, oysters, and turtles during tides inside. There is a suggestion that these fish traps may be the oldest human-made structures in the world. The age of similar fish traps is currently estimated to be up to 3,000 years.

Brewarrina Fish Traps in 2023, Wikipedia.

Another distinctive feature of Kaiadilt art, and Amy Loogatha’s in particular, is the abundant use of ochre, red, and orange. These colors likely represent the multicolored laterite patches found along the coast of Bentinck Island (Fig. 8). Laterite is a natural source of colored ochre, which women traditionally ground into a dry paste to color the rope they wound around their hips. Amy Loogatha is most inspired by these colors, and these color blocks appear most frequently in her art.

My country (c) Amy Loogatha. Courtesy of Cooee Art Leven, NSW, Accompanied by a Certificate of Authenticity from Mirndiyan Gununa, Mornington Island Art

Other motifs in Kaiadilt art carry a heavier emotional load. Triangles, rhythmic lines, and contrasting color blocks represent burrkunka—ritual scars or markings.

Burrkunka, May Moodoonuthi (1939–1983), Redot Fine Art Gallery

In traditional Kaiadilt life, scars were used for many purposes. It is important to note that the first scars a boy received were called mungurru—a word that usually means “knowledgeable, wise”. This is because these initial cuts were used to accustom boys to the greater pain they would face during initiation. A boy was cut by his maternal uncle, and a girl by her father’s full cousin, whom she called kardu (father-in-law) in anticipation of a future marriage to his son.

Other scars were made by women using sharp shells as part of the grieving process. When someone died, people would cut themselves in this way so that blood would flow from the burrkunka onto the corpse. Women would cut their thighs after the death of a husband. Cuts on visible areas were smeared with rambaramba—a widely available multicolored ochre on the island—or red mud to aid healing and give the scar a special texture.

______________________________________

Amy Loogatha and other Kaiadilt artists embody the remarkable story of the revival of a culture that was once nearly lost. Their works not only adorn gallery walls but also serve as a reminder of the importance of preserving and respecting the cultural heritage of all peoples. In an era of globalization and mass assimilation, the art of such artists plays a key role in preserving unique identities and cultural diversity worldwide.

The creativity of the Kaiadilt is not just art; it is an act of resistance and an assertion of their right to exist in a world that long ignored their culture and language. Today, thanks to people like Amy Loogatha, their art has become a powerful means of expression and preservation of ancient traditions, continuing to inspire and amaze people around the world.

The following sources were used in the preparation of this material:

Nicholas Evans, Louise Martin-Chew & Paul Memmott, The Heart of Everything. The Art and Artists of Mornington & Bentinck Islands, McCulloch & McCulloch, 2008, Melbourne.

Norman Tindale, “Geographical knowledge of the Kaiadilt people of Bentinck Island”, in Records of the South Australian Museum, 14.2, 1962, pp. 252–96.

South Australian Museum; Public Library, Museum and Art Gallery of South Australia. Records of the South Australian Museum. Adelaide: Published under the authority of the board of governors and edited by the museum director, 1918. Vol. 14. [Electronic resource]. URL: <http://biodiversitylibrary.org/permissions> (accessed: 08.06.2024).